Yikes. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2842972

Foodborne Illness

Child Obesity Clinics in England Seeing BMIs over 50

Read article at this link https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvg7w58yddgo

Yikes!

Obesity is Not a Disease

David L. Katz, MD, MPH, FACPM, FACP, FACLM is a specialist in Internal Medicine, Preventive Medicine/Public Health, and Lifestyle Medicine – globally recognized for expertise in chronic disease prevention, health promotion, and nutrition. The founding director of Yale University’s Prevention Research Center, and past president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine, Katz is the founder of the non-profit True Health Initiative, founder of Diet ID, and Chief Medical Officer for leading food-as-medicine company, Tangelo. He is a senior science advisor to Blue Zones. He holds multiple US patents, including for advances in dietary assessment. He has roughly 250 peer-reviewed publications, has authored 19 books- including multiple editions of a leading textbooks in nutrition and preventive medicine, and has earned numerous awards for his contributions to public health, including three honorary doctoral degrees.

https://www.vumedi.com/video/obesity-is-not-a-disease-so-what-is-it

Diet until proven otherwise.

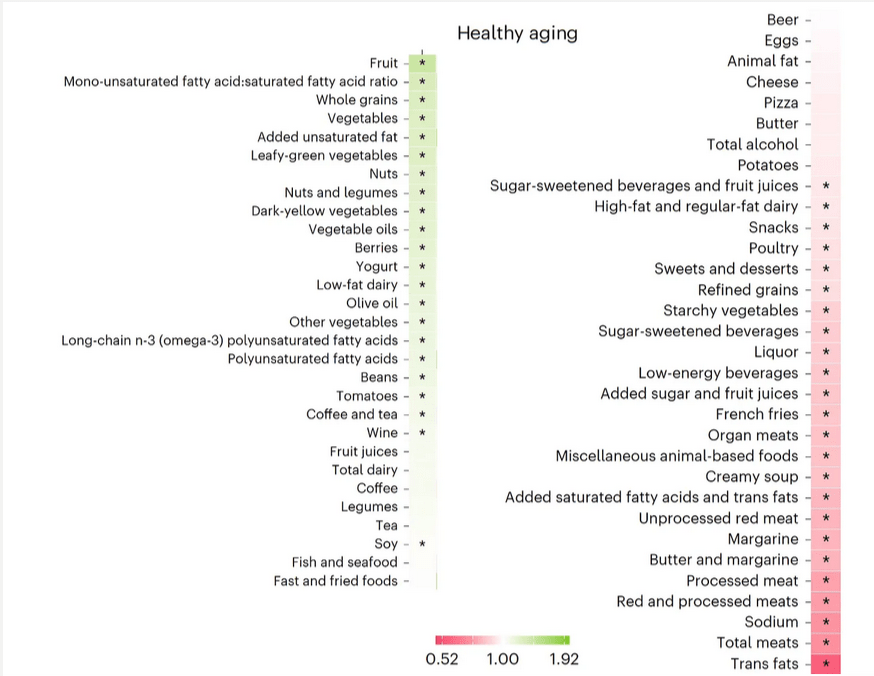

Diet and Healthy Aging

In the journal Nature Medicine this week there was an important open-access publication about a large combined cohort of over 105,000 health professionals prospectively followed for 30 years. Only 9.3% reached the age of 70 years with “healthy aging” —without 11 major chronic diseases and no impairment of cognitive or physical function or mental health. Our Diet and Healthy Aging Eric Topol, MD – https://erictopol.substack.com/p/our-diet-and-healthy-aging

Dr. Eric Topol’s assessment of this study is well balanced and thoughtfully written. His bio is here: https://www.scripps.edu/faculty/topol/

Healthy aging in this study is described as reaching age 70 without developing any of 11 major diseases: cancer (except for non-melanoma skin cancers), diabetes, heart attack, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

My Half-Birthday is coming up soon. I’ll be 70.5 years young. The biggest take home lesson for me is this:

Beer is better for you than pizza.

Dietary Approaches to Obesity Treatment

There is no single diet that can universally fit everyone for weight loss benefit.

Parmar RM, Can AS. Dietary Approaches to Obesity Treatment. [Updated 2023 Mar 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574576/ — https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574576/

Words of Wisdom from a former 370 pound human.

What worked for me may not work for you.

Keep searching for what works for you.

Find the differences that make a difference.

Good luck.

Gut Bacteria May Drive Colorectal Cancer Risk

The researchers found signs that a high-fat, low-fiber diet may increase inflammation in the gut that prevents it from naturally suppressing tumors. The cells of young people with colorectal cancer also appeared to have aged more quickly — by 15 years on average — than a person’s actual age. That’s unusual, because older people with colorectal cancer don’t have the same boost in cellular aging.

The rate of colorectal cancer among young people has been rising at an alarming rate, according to a 2023 report from the American Cancer Society. In 2019, 1 in 5 colorectal cancer cases were among people younger than 55. That’s up from 1 in 10 in 1995, which means the rate has doubled in less than 30 years. Young People’s Gut Bacteria May Drive Colorectal Cancer Risk – Medscape – June 06, 2024 — https://www.medscape.com/s/viewarticle/young-peoples-gut-bacteria-may-drive-colorectal-cancer-risk-2024a1000amd?src=rss

Yikes.

Reversing Diabetes in Alabama

Reversing type 2 diabetes through a low-carbohydrate diet is clearly an evidence-based approach. Yet, thus far, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which runs the scientific reviews for the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the nation’s top nutrition policy, has neglected to acknowledge any of the more than 100 clinical trials on this diet. In the scientific reviews currently underway for the next iteration of the guidelines, due out in 2025, the USDA has declined even to examine this scientific literature.

Reversing Diabetes in Alabama — https://www.nutritioncoalition.us/news/reversing-diabetes-in-alabama

“Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food”

Hippocrates, the father of medicine

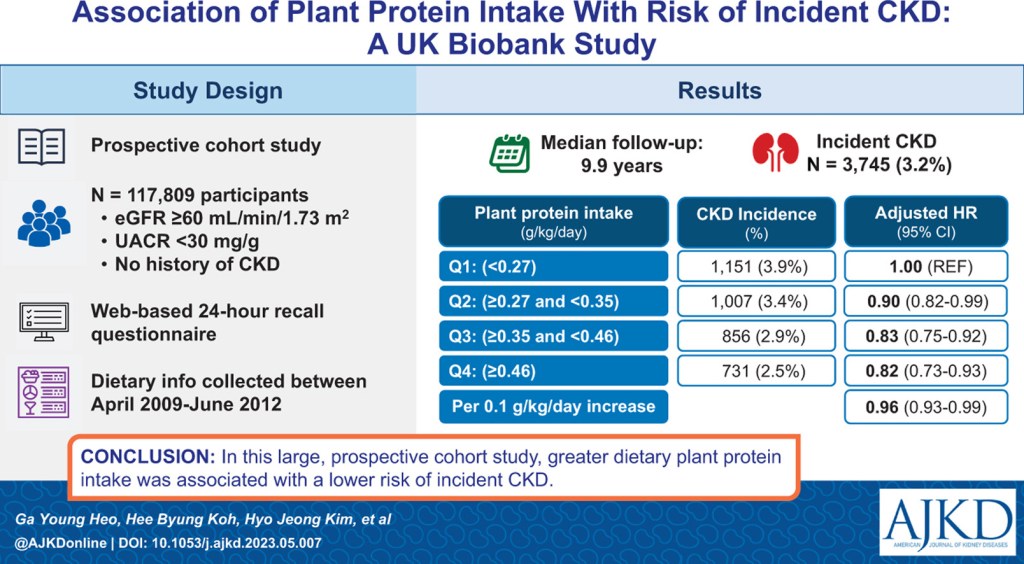

How to Keep Your Kidneys Healthy (eat more plants)

Association ofPlant Protein Intake With Risk of Incident CKD: A UK Biobank Study — https://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(23)00742-4/fulltext

Scary Charts (Beyond BMI) – 06.04.23

The value of the BMI for tracking the current epidemic of obesity is clearly illustrated in the study by Rodgers et al., which traced the change in the BMI for many subgroups of the US population from 1962 to the year 2000 [23]. (See Figure 1) They showed that the US epidemic of obesity began about 1975 in all age, sex and ethnic groups and continued over the next 25 years. This fact limits the plausible explanations for the current epidemic of obesity. Rodgers and colleagues believe that it is implausible that each age, sex and ethnic group, with massive differences in life experience and attitudes, had a simultaneous decline in willpower related to healthy nutrition or exercise, or that intrauterine exposures played a major causative role. Likewise, changes in genetic make-up are unlikely to have occurred over this short period and to have affected all age groups simultaneously. Similarly, they note that it is unlikely that any factor with a long induction period had a major role in the US epidemic. Rather, they believe that the epidemic must have been caused by factors that led to rapid population-wide changes such as changes in the food supply, and I tend to agree with their conclusion.

Beyond BMI by George A. Bray – Nutrients 2023, 15(10), 2254 – https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102254

Agree.

New Prescription for the Chronically Ill

Fresh Produce Is an Increasingly Popular Prescription for Chronically Ill Patients

By Carly Graf March 23, 2023

When Mackenzie Sachs, a registered dietitian on the Blackfeet Reservation, in northwestern Montana, sees a patient experiencing high blood pressure, diabetes, or another chronic illness, her first thought isn’t necessarily to recommend medication.

Rather, if the patient doesn’t have easy access to fruit and vegetables, she’ll enroll the person in the FAST Blackfeet produce prescription program. FAST, which stands for Food Access and Sustainability Team, provides vouchers to people who are ill or have insecure food access to reduce their cost for healthy foods. Since 2021, Sachs has recommended a fruit-and-vegetable treatment plan to 84 patients. Increased consumption of vitamins, fiber, and minerals has improved those patients’ health, she said.

“The vouchers help me feel confident that the patients will be able to buy the foods I’m recommending they eat,” she said. “I know other dietitians don’t have that assurance.”

Sachs is one of a growing number of health providers across Montana who now have the option to write a different kind of prescription — not for pills, but for produce.

The Montana Produce Prescription Collaborative, or MTPRx, brings together several nonprofits and health care providers across Montana. Led by the Community Food & Agriculture Coalition, the initiative was recently awarded a federal grant of $500,000 to support Montana produce prescription programs throughout the state over the next three years, with the goal of reaching more than 200 people across 14 counties in the first year.

Participating partners screen patients for chronic health conditions and food access. Eligible patients receive prescriptions in the form of vouchers or coupons for fresh fruits and vegetables that can be redeemed at farmers markets, food banks, and stores. During the winter months, when many farmers markets close, MTPRx partners rely more heavily on stores, food banks, and nonprofit food organizations to get fruits and vegetables to patients.

The irony is that rural areas, where food is often grown, can also be food deserts for their residents. Katie Garfield, a researcher and clinical instructor with Harvard’s Food is Medicine project, said produce prescription programs in rural areas are less likely than others to have reliable access to produce through grocers or other retailers. A report from No Kid Hungry concluded 91% of the counties nationwide whose residents have the most difficulty accessing adequate and nutritious food are rural.

“Diet-related chronic illness is really an epidemic in the United States,” Garfield said. “Those high rates of chronic conditions are associated with huge human and economic costs. The idea of being able to bend the curve of diet-related chronic disease needs to be at the forefront of health care policy right now.”

Produce prescription programs have been around since the 1960s, when Dr. Jack Geiger opened a clinic in Mound Bayou, a small city in the Mississippi Delta. There, Dr. Geiger saw the need for “social medicine” to treat the chronic health conditions he saw, many the result of poverty. He prescribed food to families with malnourished children and paid for it out of the clinic’s pharmacy budget.

A study by the consulting firm DAISA Enterprises identified 108 produce prescription programs in the U.S., all partnered with health care facilities, that launched between 2010 and 2020, with 30% in the Northeast and 28% in the Midwest. Early results show the promise of integrating produce into a clinician-guided treatment plan, but the viability of the approach is less proven in rural communities such as many of those in Montana.

In Montana, 31,000 children do not have consistent access to food, according to the Montana Food Bank Network. Half of the state’s 56 counties are considered food deserts, where low-income residents must travel more than 10 miles to the nearest supermarket — which is one definition the U.S Department of Agriculture uses for low food access in a rural area.

Research shows long travel distances and lack of transportation are significant barriers to accessing healthy food.

“Living in an agriculturally rich community, it’s easy to assume everyone has access,” said Gretchen Boyer, executive director of Land to Hand Montana. The organization works with nearby health care system Logan Health to provide more than 100 people with regular produce allotments.

“Food and nutritional insecurity are rampant everywhere, and if you grow up in generational poverty you probably haven’t had access to fruits and vegetables at a regular rate your whole life,” Boyer said.

More than 9% of Montana adults have Type 2 diabetes and nearly 35% are pre-diabetic, according to Merry Hutton, regional director of community health investment for Providence, a health care provider that operates clinics throughout western Montana and is one of the MTPRx clinical partners.

Brittany Coburn, a family nurse practitioner at Logan Health, sees these conditions often in the population she serves, but she believes produce prescriptions have tremendous capacity to improve patients’ health.

“Real food matters and increasing fruits and veggies can reverse some forms of diabetes, eliminate elevated cholesterol, and impact blood pressure in a positive way,” she said.

Produce prescription programs have the potential to reduce the costs of treating chronic health conditions that overburden the broader health care system.

“If we treat food as part of health care treatment and prevention plans, we are going to get improved outcomes and reduced health care costs,” Garfield said. “If diet is driving health outcomes in the United States, then diet needs to be a centerpiece of health policy moving forward. Otherwise, it’s a missed opportunity.”

The question is, Do food prescription initiatives work? They typically lack the funding needed to foster long-term, sustainable change, and they often fail to track data that shows the relationship between increased produce consumption and improved health, according to a comprehensive survey of over 6,000 studies on such programs.

Data collection is key for MTPRx, and partners and health care providers track how participation in the program influences participants’ essential health indicators such as blood sugar, lipids, and cholesterol, organizers said.

“We really want to see these results and use them to make this more of a norm,” said Bridget McDonald, the MTPRx program director at CFAC. “We want to make the ‘food is medicine’ movement mainstream.”

Sachs acknowledged that “some conditions can’t usually be reversed,” which means some patients may need medication too.

However, MTPRx partners hope to make the case that produce prescriptions should be considered a viable clinical intervention on a larger scale.

“Together, we may be able to advocate for funding and policy change,” Sachs said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.